اینجا میان توانبخشان

Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder is one of the most sophisticated and complicated joints of the body:

It has the greatest range of motion of any joint in the body allowing complete global movement allowing you to position the hand anywhere in space.

- The coordinated activity of numerous muscles working together in set patterns is required to produce this motion

- It is made up of FOUR joints and FIVE linked bone groups which are related and work together.

- To allow so much movement the joints need to be "free" to move, therefore the shoulder should be unstable; However a series of complex ligaments and muscle keep it in joint.

Because the shoulder is such a unique joint it is also prone to unique and complex problems. In fact it would be more correct to call it the SHOULDER COMPLEX.

This section will hopefully explain some of the terminology you might hear and relate this to disorders of the shoulder complex. Understanding how the different layers of the shoulder are built and connected can help you understand how the shoulder works and is affected by injury and overuse.

The deepest layer includes the bones and the joints of the shoulder.

The next layer is made up of the ligaments of the joints.

The tendons and the muscles come next.

The nerves supply all the stuctures above and make them work.

Bones & Joints of the Shoulder

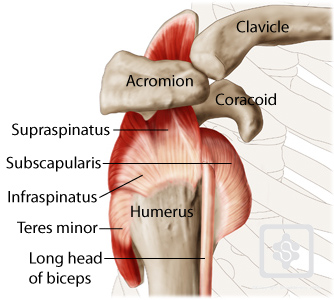

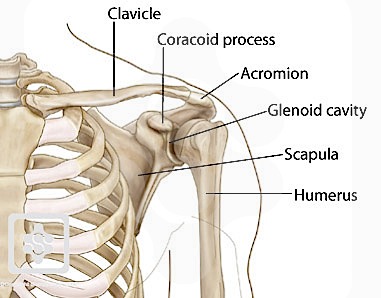

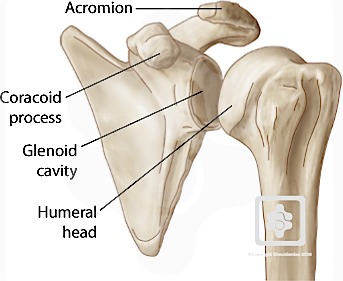

The bones of the shoulder consist of the humerus (the upper arm bone), the scapula (the shoulder blade), and the clavicle (the collar bone).

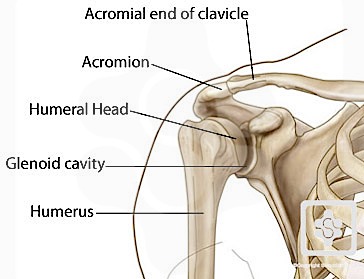

The clavicle is the only bony attachment between the trunk and the upper limb. It forms the front portion of the shoulder girdle and is palpable along its entire length with a gentle S-shaped contour.The clavicle articulates at one end with the sternum (chest bone) and with the acromion of the scapula at the other. This articulation between the acromial end of the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula forms the roof of the shoulder.

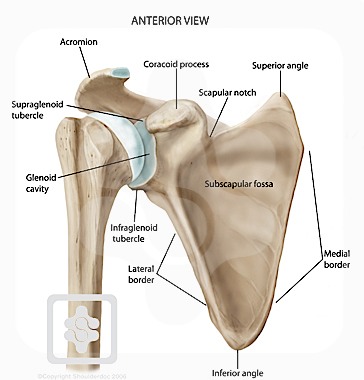

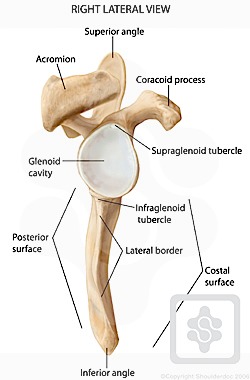

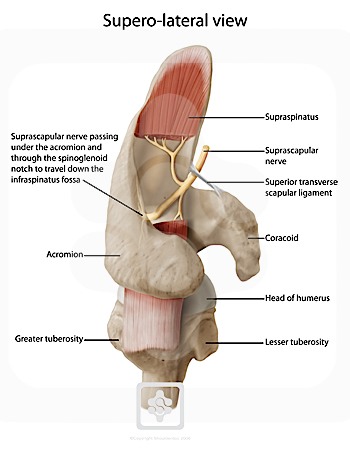

The scapula is a large, flat triangular bone with three processes called the acromion, spine and coracoid process . It forms the back portion of the shoulder girdle. The spine (which is located at the back of the scapula) and the acromion can be readily palpated on a patient.

The flat blade of the scapula glides along the back of the chest allowing for extended movement of the arm. The coracoid process is a thick curved structure that projects from the scapula and is the attachment point of ligaments and muscles.

The scapula is also marked by a shallow, somewhat comma-shaped glenoid cavity , which articulates with the head of the humerus.

The top end of the humerus consists of the head, the neck, the greater and lesser tubercles, and the shaft. The head is half-spherical in shape and projects into the glenoid cavity. The neck lies between the head and the greater and lesser tubercles. The greater and lesser tubercles are prominent landmarks on the humerus and serve as attachment sites for the rotator cuff muscles.

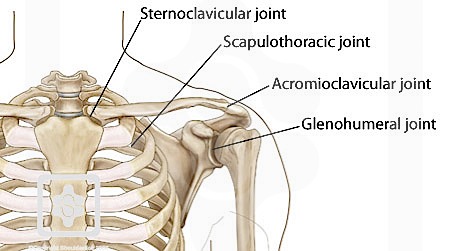

There are four joints making up the "shoulder joint":

- The shoulder joint itself known as the Glenohumeral joint, (is a ball and socket articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula)

- The acromioclavicular (AC) joint (where the clavicle meets the acromion of the scapula)

- The sternoclavicular (SC) joint (where the clavicle meets the chest bone [sternum])

- The scapulothoracic joint (where the scapula meets with the ribs at the back of the chest)

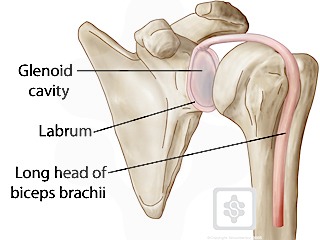

Note how the ball ( head ) of the humerus fits into a shallow socket on the scapula called the glenoid . One can see that this ball does not fit into the glenoid cup at all; this allows for the wide range of movement provided by the shoulder, at the cost of skeletal stability. Joint stability is provided instead by the rotator cuff muscles , related bony processes and glenohumeral ligaments.

Shoulder Ligaments

ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. There are several important ligaments in the shoulder.

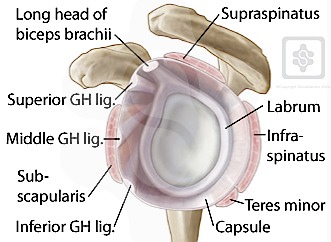

Glenohumeral ligaments (GHL):

A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint. In the shoulder, the joint capsule is formed by a group of ligaments that connect the humerus to the glenoid. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the shoulder. They are the superior, middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments. They help hold the shoulder in place and keep it from dislocating .

Coraco-acromial ligament (CAL):

Another ligament links the coracoid to the acromion - coracoacromial ligament (CAL). This ligament can thicken and cause Impingement Syndrome

Coraco-clavicular ligaments (CCL):

These two ligaments (trapezoid and conoid ligaments) attach the clavicle coracoid process of the scapula. These tiny ligaments (with the acomioclavicular joint) play an important role in keeping the scapula attached to the clavicle and thus keeping your shoulder "square". They carry a massive load and are extremely strong.

A fall on the point of the shoulder can rupture these ligaments with dislocation of the AC Joint .

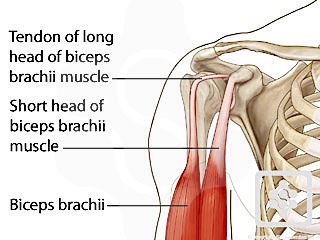

Transverse Humeral ligament (THL) :Holds the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii muscle in the groove between the greater and lesser tubercle on the humerus (intertubercular sulcus).

Shoulder Tendons

tendons are extensions of muscles that attach muscles to bone. Muscles move the bones by pulling on the tendons.

Rotator Cuff:The rotator cuff tendons are a group of four tendons that connect the deepest layer of muscles to the humerus. They are the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles.

These are (from front to back):

The supraspinatus is the most commonly affected tendon, both by overuse and trauma. It is the muscle that lifts your arm out to the side (a very important movement for most daily taks). Injury to the tendon can result in a Rotator Cuff Tear. Overuse can lead to Subacromial Impingement.

The Long Head of Biceps (LHB) is a very important tendon that travels through the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint). The biceps tendon begins at the top of the shoulder socket (the glenoid) and then passes across the front of the shoulder to connect to the biceps muscle. (The biceps is the muscle that weightlifters are always showing off).

Nerves of the Shoulder

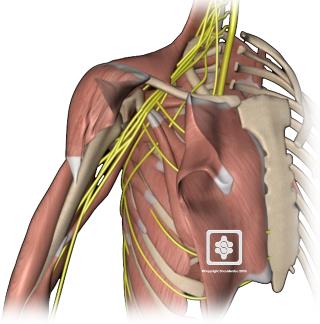

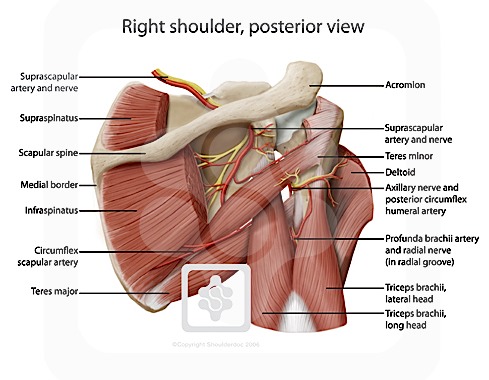

All of the nerves that travel down the arm pass through the axilla (the armpit) just under the shoulder joint and are known as the Brachial Plexus before dividing into the individual nerves. These nerves carry the signals from the brain to the muscles that move the arm. The nerves carry signals back to the brain about sensations such as touch, pain, and temperature.

The Brachial Plexus is made up of a large number of nerves that supply the arm with it"s ability to function and feel. Nerve problems around the shoulder are rare, but the most commonly affected of these nerves are:

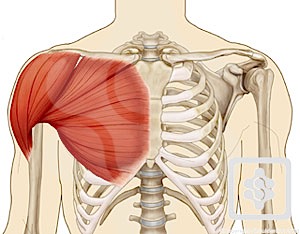

- 1.Axillary Nerve - supplies the Deltoid muscle. Most commonly stretched with shoulder dislocations.

- 2.Long Thoracic Nerve - supplies Serratus Anterior muscle and can cause Winging of the Shoulder

- 3.Suprascapular Nerve - supplies supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and can be entrapped or diseased

- 4.Musculocutaneous Nerve - supplies the Biceps muscle and can rarely be injured at surgery

Brachial Neuritis (also known as Parsonage-Turners Syndrome) is an uncommon disease where the Brachial Plexus nerves are weakened, causing muscle wasting and weakness of the shoulder.

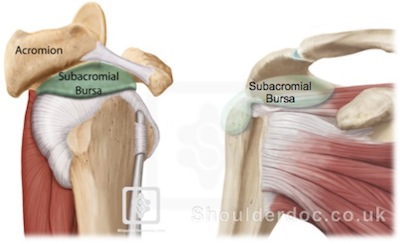

Shoulder Bursae

Sandwiched between the rotator cuff muscles and the outer layer of large bulky muscles is a structure known as the subacromial bursa. Bursae are everywhere in the body. They are found wherever two body parts move against one another and there is no joint to reduce the friction. A bursa is simply a sac between two moving surfaces that contains a small amount of lubricating fluid.

Think of a bursa like this: If you press your hands together and slide them against one another, you produce some friction. In fact, when your hands are cold you may rub them together briskly to create heat from the friction. Now imagine that you hold in your hands a small plastic sack that contains a few drops of salad oil. This sack would let your hands glide freely against each other without a great deal of friction.

Inflammation and swelling of the subacromial bursa is known as bursitis and associated with Subacromial Impingement of the Shoulder

Glenoid Labrum

The shoulder joint is considered a "ball and socket" joint, however, the "socket" (the glenoid fossa of the scapula) is quite shallow and small, covering at most only a third of the "ball" (the head of the humerus). The socket is deepened by the glenoid labrum.

The glenoid labrum is similar to the meniscus of the knee. It is a fibro-cartilaginous rubbery structure which encircles the glenoid cavity deepening the socket providing static stability to the glenohumeral joint. It acts and looks almost like a washer, sealing the two sides of the joint together.

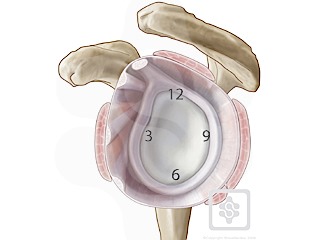

The labrum is described like a clock face with 12 o"clock being at the top (superior), 3 o"clock at the front (anterior), 6 o"clock at the bottom (inferior) and 9 o"clock at the back (posterior). Clinicans may reverse the 3 o"clock and 9 o"clock for left shoulder describing 3 o"clock at the back. This can be confusing, so the European Society of Shoulder & Elbow Surgeons (SECEC) has agreed to keep 3 o"clock at the front for either shoulder.

An injury to the shoulder with shear forces either in the anterior or posterior or superior directions leads to a labral tear in the affected area. An injury between 3 and 6 o"clock is known as a Bankart tear . superior labral injury is known as a SLAP tear (superior labral anteroposterior). A posterior tear of the posterior labrum is known as a posterior labral tear of reverse Bankart lesion.

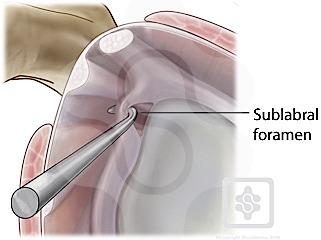

Sublabral foramen are anatomical variants, which is where the labrum can be "lifted up" between 12 and 3 o"clock. It should not be confused with a labral tear, as its edge is clearly round and smooth and not red and ragged.

The biceps muscle has two tendons at the shoulder, called the Long Head and Short Head.

نوشته شده توسط زهرا تجملی در دوشنبه 90/8/16 و ساعت 9:22 عصر | نظرات دیگران()

نوشته شده توسط زهرا تجملی در دوشنبه 90/8/16 و ساعت 9:22 عصر | نظرات دیگران()